ON NICK DRAKE & ‘BRYTER LAYTER’

Nick Drake

Bryter Layter Boxset

(Commercial Marketing)

“I think that’s one of the problems with Nick’s legacy, if there is a problem. I get sent tapes just by people out there who have a guitar and want to write songs, and they are very touched by Nick Drake and they make a demo tape, and they send it to Nick Drake’s producer and they say, “What do you think of this? I love Nick Drake, can’t you hear it in my music?” And 99 percent of those tapes that I get — or electronic submissions these days — are breathy vocals, Aparicio guitars and form without essence. There’s nothing in there of the wit or the subtlety of Nick, or the sophistication of his music. What drew me to Nick wasn’t the subject matter, but the tremendous originality and freshness of the musical vision. And it’s always been mysterious” — Joe Boyd

There is an epidemic out there, a nasty rash. Even Simon Cowell’s noticed. It would seem that the singer-songwriter is everywhere, all so similar, all so dull, all so slimily seeking our fondness. Everywhere you turn there is someone bearded, someone earnest, someone with passion trying to sing you a song from the heart. The song is nearly always the same. It will be about ‘holding on’. It will be about ‘letting things go’. It will be about ‘staying together’. Not a single word will be poetic, although the writer will frequently mistake the use of scientific or managerial speak in the lyrics as being poetic. It will take a condescending look at a ‘character’, mistaking pity for compassion and metaphor for depth. It will be the very best the writer and singer can do. And that is why these people need informing of something. That they are all, convincing though the mutual backslaps and incestuousness is — suffering from a severe type of mental illness, the kind of Aspergers-delusion that in any other walk of life would require a psyche-evaluation and a recommended sabbatical for six-months to a year.

I know some of these people. Every city has them, their little community of folkies and troubadours, who all go to the same pubs on the same night to watch each other close their eyes and be transported within the ever-engrossing confines of their windswept souls. Together they keep their delusions alive, that they’re cutting away the flab and fanny that chokes meaning in modern industrial pop and returning things to an agrarian wood’n’wire purity, a place where the city can be risen above even as it’s so ‘bravely’ explored. There’s several fronts to this arrogance — first and foremost the supposed gallantry of ‘writing their own songs’ immediately auto-annointing themselves with the burnished glow of self-sufficiency, their superiority to those puppets who sing only other people’s words, play other people’s tunes, y’know like Elvis, Frank Sinatra. These folk have the guts and grit and dauntlessness to write all their own songs, y’know, like Nickelback, Ed Sheeran. There’s also the further arrogance that can only come from a fundamental misunderstanding of what music’s all about — collaboration between people- this rather modern idea that the singer songwriter stands alone, works on their vision alone, that we are lucky to bear witness to such purely committed artistry, uncut as it is by the concision or urge to edit that others would bring. Finally there’s the arrogance in assuming that what people want to hear is songs ‘from the heart’, which usually means an incredibly constricted set of cliches have to be in place for that song’s writing and execution. Politically it can be extroverted yet must always return to a deeper message of survival DESPITE the interference of others, personally it has to arrive at a moment where the singer figures it all out, self-diagnoses his or herself and prescribes a better future or a self-satisfied stasis. It’s from their heart and you will listen, regardless of any selfishness behind the expression, attuned as you are to the lazy universality of the lyrics, the ease of empathy all that vaguery about confinement versus the open road inspires. Vocally the singer must twitch, at carefully timed (“quirky) moments of particular import, into their ‘other’ voice, the one they only flex when they’re really feeling it, tapping their internal maelstrom for the rawest emotion, that moment where all the men get to sound like Jeff Buckley and all the women set their larynxes to ‘foghorn’. In the delivery of their songs, eyes will be constantly closed, heads will sway, locked in on their own genius, rarely making contact with an audience who should feel honoured to be witness to such courage and daring.

That inflated sense of truth and connection doesn’t just animate the performers, it also brings together the audience, galvanises their sense of commitment to an entirely urban bucolic ideal of ‘what music is all about’, the tacit unspoken critique and conservative fear of the real city and all that problematic post-60s diversity that despoiled and defiled the true troubadour impulse.

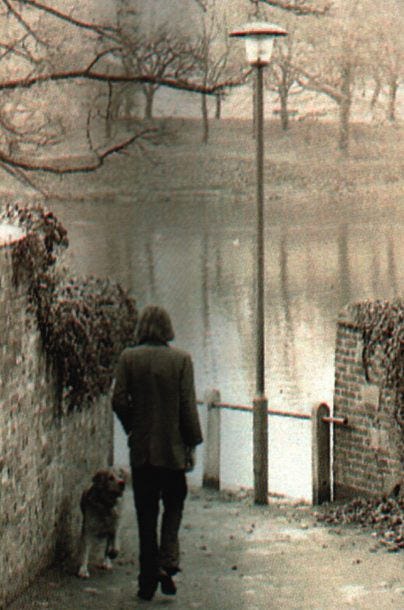

To a tiny extent you can blame people like poor old Nick Drake for these kind of delusions. Drake was off on his own, toted a tape, he played a 24 hour festival with Fairport, got his tape to Joe Boyd, and Boyd knew then something special was happening. As Boyd points out though, this gives too many people the idea that in their seclusion, in their endlessly self-important, humourless explorations of their innards they’ll find something unique that needs hearing. Whereas what actually emerges as important whenever you listen to Drake, particularly ‘Bryter Layter’, his most interesting album, is that other people’s interference was crucial, and that really what Drake was can’t be reduced to so brutishly simplistic and loaded a formulation as ‘singer-songwriter’. He’s far too odd still, far too different and special still despite the legion of lunkheaded copyists he’s inspired, to be so easily summated, or so confined to the tools he used or the supposed lack-of-image he put across (which of course becomes its own image).

For starters, his guitar playing. If you’re ‘committed’ a music-fan enough to only experience one sense at a time then you’ll see on the cover that he’s playing an acoustic guitar, but if you’re a human being you’ll realise — my god WHAT a thing he turns it into. Not simply an up and down thing of strum, or a finger picking thing of detail but the fretboard as dancefloor, the soundboard as rumpus room, a labarynth of geometry and shadow, a rhythm section all to itself. One of the funkiest guitarists of all time and the only other British people I could remotely compare his playing to is John Martyn and Vini Reilly — players so unique that a lifetime spent trying to emulate them would be a lifetime wasted. Anyone who’s ever tried to learn how to play a Nick Drake song knows that it’s not contained in the chords, or the structure. It’s contained in the unplaceable tunings, the shape of the way he leans into what he’s playing, the way his fingers, deep within themselves, are actually possessed of an almost frighteningly inhuman mechanical grace, the way he absolutely resolutely refuses to play everything he could be playing. And where alot of musicians allow their bad cliched habits as players inform their equally uninteresting songwriting, so Drake’s songs are always pitched in a totally unique place, somewhere between reverie and resistance, somewhere between being buffeted away by a breeze or a whim and being the heaviest blackest darkest shit you’ve ever heard in your life. There’s a private humour to Nick Drake’s songs that allows that heaviness to not hurt or become wearisome, there’s a cellular bleakness that stops it being all air and light, that slowly has his vision closing in on you, closing you down, enveloping you. ‘Bryter Layter’ was the first Nick Drake album I ever heard, consequently it’s my favourite, but I think beyond that initial way his voice just made me crumble I think it’s my favourite cos it’s his poppiest, his lushest, the one where you feel he’s most part of the world. ‘Introduction’ I used to put on as a little bathe of sunshine every morning, still it’s one of the most evocative openings to an album you’ll hear, cracking your shell, letting the rays in, and the clouds. Listen to Jake Bugg’s fuckawful pointless cover of ‘Hazey Jane II’ and then listen to Drake’s and you can hear exactly how much is going on here more than chords and words. Richard Thompson’s guitar is key as it is throughout, sliding things round the corner, fracturing and forming the shapes, Robert Kirby’s simply gorgeous strings (best ‘rock’-band string-arrangement this side of Paul Buckmaster or Tony Visconti) force Drake out of himself and out into the street. ‘Chime Of A City Clock’ & the heart-rending ‘One Of These Things First’ both gently remind you just exactly what an astonishing riddim-machine Nick was, how vital Dave Pegg’s bass is throughout, what a genius move it was getting Beach Boys veteran Mike Kowalski in to do some sunkissed shuffle & stealth.

“Hazey Jane I” is the moment for me when ‘Bryter Layter’ stops just being dazzling and starts negotiating its place in heaven, Dave Mattacks giving the drums the same sense of rippling endless fade-out that Paul Thompson does in the last minutes of Roxy’s ‘For Your Pleasure’, Pegg, Drake & Kirby making the rest a swish of zephyrs and brokenness. ‘Bryter Layter’, the title track is twisted supermarket muzak, the most unsettling warp of almost too-sweet melody my young head had heard since the 2nd side of ‘Forever Changes’. John Cale’s viola and harpsichord on ‘Fly’ are just exquisite, working with Pegg’s fantastically medieval low-end to lend Drake the poet-knightly air of the Stones ‘Lady Jane’ with none of the meanness of spirit, just a beautiful proneness and wilted need that suits the words and the voice perfectly. Boyd’s brilliance at bringing the right people together in service of the songs, not the artist, works so brilliantly throughout ‘Bryter Layter’ it becomes less and less like a singer-songwriter’s album, more and more like an ensemble piece, albeit an ensemble who have to follow the curious mix of clear-eyed hardboiledness and red-eyed dissipation that Drake’s songs inhabit. All the words I’ve ever heard to describe Drake, ‘ethereal’, ‘airy’, ‘introspective’ seem to me to be reflecting a response to his voice rather than the way his songs actually come across — this idea that Drake’s natural shyness leads to an obscurity of purpose or meaning is demolished through ‘Bryter Layter’s stunning closing side, perhaps suggesting that it’s always a mistake to think the shy boy can’t be a monster on the quiet, or that a naturally weak voice can’t dominate your day. Drake’s voice sounds anything but non-committal, has the same unbridled sense of personality and difficulty and bloody-minded naturalism that you sense Drake was always possesed with. So ‘Poor Boy’ is never in danger of being earnest, is always taking the piss out of its protaganist and out of you, P.P Arnold & Doris Troy’s sweet backing vocals cutting loose on the chump, skewering his self-pity. “Northern Sky” seems to want to wipe the slate clean, clear the clutter of poesy any songwriter finds him/herself backed into, start afresh with a “new mind’s eye”, Cale’s wondrous celeste adding to that sense of rebirth at the dead-end of a loveless lifetime, Drake now seemingly getting down to the basic yet inherently ambiguous statements of hope and irredeemable darkness the whole album’s been playing with. And ‘Sunday’ is just the perfect closer — back in the strangely off-key muzak world of the title track, suffused with a warmth that’s pure Bosworth archive from Kirby’s hanging strings, the flute at times embodying what you feel Drake might have sung, at times slipping free and skipping down the road with a naivete and innocence you couldn’t credit him with — it leaves you wondering who the hell is this Nick Drake guy and why has he chosen to bookend and sandwich his LP with these moments of purely instrumental lissomness when you’ve been told he was a singer-songwriter, someone who meant it man, someone who played from the heart. Throughout ‘Bryter Layter’ it’s clear he’s playing, writing, from a way more twisted, more open, more generous place than that.

A word about the box. I don’t have it. I don’t care about it and neither should you. Drake’s is a story that needs no more fleshing out (and Brad fucking Pitt should be banned from ever talking about him again), and requires no more artifacts beyond the records as they are. They themselves are inexhaustible and infinite enough to be getting along with, and ticket stubs, posters, extra artwork, free downloads, sketches, nuts’n’bolts demystifications I can do without. I’m utterly disinterested in Nick Drake the man, just as I’m utterly disinterested in all singers ‘from the heart’, all musicians who see music as a way of keeping a journal, inflicting their self-absorption on the rest of us. I’m still, despite the unpleasant speculations and romanticising of the rock ‘audience’, totally fascinated by the sophistication, ease, and suggestiveness of Drake’s music. His depression and demise are as tragic to me as any persons passing, but no-one should allow them to in any way affect their enjoyment of the things he made, cos his music in its sheer intransigent existence absolutely denies the sadness, denies whatever ‘message’ you might draw from the way he ended up. What you hear on ‘Bryter Layter’ is the man at play, in delight and wonder, exercising his powers to their fullest in collaboration with some of pop’s brightest sparks and most humane spirits. Nick Drake, though so often used as emblematic of some auteur spirit, especially by his fans who’ve “discovered” him through something other than the records, is, like any interesting musician proof of the exact opposite, that the best artists need others to truly bring out what isn’t inside them, what’s more than they contain, that you only get to be thoroughly honest when you’re being honest about your own inherent dishonesty, unreal about your reality, real about your unreality, and music is the perfect artform to express that essential dualism so many straight-ahead singer-songwriters are missing. In comparison to Drake’s shy reticence, the confidence and sickly self-regard of his self-appointed descendants is a natural consequence of their musical myopia and their pipsqueak souls. Drake’s harder, tougher, funnier, than any of them, and ‘Bryter Layter’ is his most welcoming and giving statement. If songs were lines in a conversation the situation would be fine. It aint, and Drake knew it, knew how much more songs could be, how much more his songs had to be. Love it, and live in here forever.